Functional disorders

Introduction

‘Functional disorder’ is an umbrella term for a group of recognisable medical conditions which are thought to be due to changes to the functioning of the systems of the body rather than due to a disease affecting the structure of the body. Functional disorders are common and complex phenomena that pose challenges to medical systems. Traditionally in modern medicine, the body is thought of as consisting of different organ systems, but it is less well understood how the systems interconnect or communicate. Functional disorders can affect the interplay of several organ systems (for example gastrointestinal, respiratory, musculoskeletal or neurological) leading to multiple and variable symptoms, although sometimes there can be a single prominent symptom or organ system affected.

Definition

Functional disorders are mostly understood as conditions characterised by:

- persistent and troublesome symptoms

- associated with impairment or disability

- where the pathophysiological basis is related to problems with the functioning and communication of the body systems (as opposed to disease affecting the structure of organs or tissues).

Most symptoms that are caused by physical/structural disease can also be caused by a functional disorder. There are many examples of symptoms that individuals may experience, some of these include pain, fatigue, weakness, shortness of breath or bowel problems. Because of this, individuals often undergo many investigations before the diagnosis is clear. Though research is growing around explanatory models that support the understanding of functional disorders, structural scans such as MRIs, or laboratory investigation such as blood tests do not usually explain the symptoms or the symptom burden. This difficulty in identifying the processes underlying the symptoms of functional disorders has often resulted in these conditions being misunderstood and sometimes stigmatised within medicine and society.

Functional disorders can affect individuals of all ages, ethnic groups and socioeconomic backgrounds. Chronic courses of disorders are common and significantly impair quality of life, and are associated with high healthcare costs (Konnopka et al 2012). However, the symptoms themselves are not a threat to life, and are considered modifiable with treatment. There is a lack of specialised treatment services for functional disorders in some countries; however the landscape in this area is changing. Research is also growing in this area, and it is hoped that the implementation of robust science driven research will allow effective supports for individuals with functional disorders to develop.

There are many different functional disorder diagnoses that might be given depending on the symptom or syndrome that is most troublesome. A syndrome is a collection of symptoms - these may be known as “Functional Somatic Syndromes”. Examples of these include; Irritable Bowel Syndrome (gastrointestinal symptoms), some persistent fatigue conditions, Chronic Pain syndromes, such as Chronic Widespread Pain (Fibromyalgia), and Functional Neurological Disorder. Single symptoms may also be assigned a diagnostic label, for example “functional chest pain”, “functional constipation” or “functional seizures”.

More accurately these conditions could be called ‘Functional Somatic Disorders’. Somatic means ‘of the body’. This is to differentiate functional somatic disorders from psychiatric illnesses which have historically also been considered as functional disorders in some classification systems, as they often fulfil the criteria above. From now on, this article refers primarily to functional disorders in which the primary troubling symptoms are generally understood as originating in the body.

Overlap

Although an individual may be diagnosed with a single functional syndrome, there is overlap in symptoms between all the functional disorder diagnoses. For example, it is not uncommon to have a diagnosis of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) and chronic widespread pain/fibromyalgia (Wessely et al 1999). All functional disorders share risk factors and factors that contribute to their persistence. Approaches to functional disorders have traditionally differed between medical specialties. Increasingly researchers and clinicians are recognising the relationships between these syndromes.

Terminology and diagnostic criteria

The terminology for functional disorders has long been fraught with confusion and controversy, with many different terms used to describe them. Sometimes functional disorders are equated or mistakenly confused with diagnoses like category of “somatoform disorders”, “medically unexplained symptoms”, “psychogenic symptoms” or “conversion disorders”. However, this is not correct, functional disorders and the aforementioned diagnosis designations are not identical and designate different clusters of symptoms. Of note, some of these terms are now no longer thought of as accurate, and are considered by many to be stigmatising (Barron and Rotge, 2019).

Currently, the 11th version of the International Classification System of Diseases (ICD-11) has specific diagnostic criteria for certain disorders which would be considered by many clinicians to be functional somatic disorders, such as IBS or chronic widespread pain/fibromyalgia, and dissociative neurological symptom disorder (WHO, 2022).

There has been a tradition of a separate diagnostic classification systems within medical and mental disorder classifications. In the 5th edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) the older term “somatoform” (DSM-IV) has been replaced by “somatic symptom disorder”, which is a disorder characterised by persistent somatic (physical) symptom(s ), and associated psychological problems to the degree that it interferes with daily functioning and causes distress. (APA, 2022). Bodily distress disorder is a related term in the ICD-11. (WHO, 2022). Somatic symptom disorder and bodily distress disorder have significant overlap with functional disorders and are often assigned if someone would benefit from psychological therapies addressing psychological or behavioural factors which contribute to the persistence of symptoms. Note however that people with symptoms partly explained by structural disease (for example cancer) may also meet the criteria for diagnosis of functional disorders, somatic symptom disorder and bodily distress disorder (Löwe et al., 2022).

Prevalence - how common are functional (somatic) disorders?

The estimated prevalence varies widely depending on the underlying predominant symptom or syndrome. In clinical populations, functional disorders are common and have been found to present in around one-third of consultations in both specialist practice (Nimnuan 2001) and primary care (Haller et al. 2015).

Rates differ in the clinical population compared with the general population, and will vary depending on the criteria used to make the diagnosis. For example, irritable bowel syndrome is thought to affect 4.1% (Sperber et al., 2011), and fibromyalgia 0.2-11.4% of the global population (Marques et al. 2017).

A recent large study carried out on population samples in Denmark showed the following: In total, 16.3% of adults reported symptoms fulfilling the criteria for at least one Functional Somatic Syndrome, and 16.1% fulfilled criteria for Bodily Distress Syndrome (Petersen et al 2019).

Explanatory Models/Causes

There are explanatory models that support our understanding of functional disorders, and there are usually multiple and complex factors involved in individual symptom development. Factors contributing to the disorder require consideration of factors which relate to that individual’s biomedical, psychological, social, and material environment - necessitating a personalised, tailored approach.

Healthcare professionals might find it useful to consider three main categories of factors: predisposing, precipitating, and perpetuating (contributing) factors.

Predisposing factors: these are factors that make the person more vulnerable to the onset of a functional disorder; and include biological, psychological and social factors. Like all health conditions, some people are probably predisposed to develop functional disorders due to their genetic make-up. However, no single genes have been identified that are associated with functional disorders. Epigenetic mechanisms (mechanisms that affect interaction of genes with their environment) are likely to be important, and have been studied in relation to the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal Axis (Tak et al, 2011). In addition to genetics/epigenetic changes, other predisposing factors include current or prior somatic/physical illness or injury, and endocrine, immunological or microbial factors (Löwe et al 2022). Functional disorders are diagnosed more frequently in female patients (Kingma et al 2013). The reasons for this are complex and multifactorial, likely to include both biological and social factors. Female sex hormones might affect the functioning of the immune system for example (Thomas et al., 2022) . Medical bias possibly contributes to the sex differences in diagnosis: women are more likely to be diagnosed than men with a functional disorder by doctors (Claréus, Benjamin, and Renström, 2019).

People with functional disorders also have higher rates of previous mental and physical health conditions, including depression and anxiety disorders, Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, Multiple Sclerosis and Epilepsy (Cohen et al., 2002; Garakani et al., 2003; Stone et al 2011). Personality style has been suggested as a risk factor in the development of functional disorders but the effect of any individual personality trait is variable and weak (Macina et al. 2021, Kato et al. 2006). Alexithymia (difficulties recognising and naming emotions) has been widely studied in patients with functional disorders and is sometimes addressed as part of treatment (Porcelli et al., 2003). Migration, cultural and family understanding of illness, are also factors that influence the chance of an individual developing a functional disorder (Isaac M. et al., 1995) . Being exposed to illness in the family when you are growing up or having parents who are healthcare professionals are sometimes considered risk factors. Adverse childhood experiences and traumatic experiences of all kinds are known important risk factors (Bradford et al, 2012; Cohen et al 2002; Ludwig 2018).

Precipitating factors: these are the factors that for some patients appear to trigger the onset of a functional disorder. Typically, these involve either an acute cause of physical or emotional stress, for example an operation, a viral illness, a car accident, a sudden bereavement, or a period of intense and prolonged overload of chronic stressors (for example relationship difficulties, job or financial stress, or caring responsibilities). Not all affected individuals will be able to identify obvious precipitating factors and some functional disorders develop gradually over time.

Perpetuating factors (Illness mechanisms): These are the factors that contribute to the development of functional disorder as a persistent condition and maintaining symptoms. These can include the condition of the physiological systems including the immune and neuroimmune systems, the endocrine system, the musculoskeletal system, the sleep-wake cycle, the brain and nervous system, the person’s thoughts and experience, his/her experience of the body, social situation and environment. All these layers interact with each other. Illness mechanisms are important therapeutically as they are seen as potential targets of treatment (Kozlowska 2013).

The exact illness mechanisms that are responsible for maintaining an individual’s functional disorder should be considered on an individual basis. However, various models have been suggested to account for how symptoms develop and continue. For some people there seems to be a process of central-sensitisation (Bourke et al., 2015; Nijs et al., 2011), chronic low grade inflammation (Lacourt et al., 2018) or altered stress reactivity mediated through the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis (Fischer et al., 2022). For some people attentional mechanisms are likely to be important. (Barsky et al., 1988) . Commonly, illness-perceptions or behaviours and expectations (Henningsen, Van den Bergh et al. 2018 ) contribute to maintaining an impaired physiological condition.

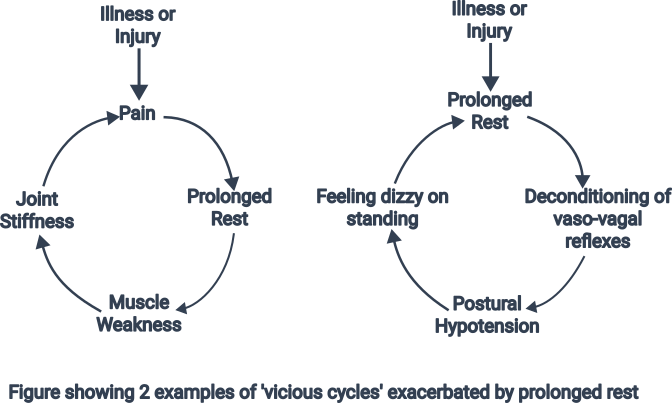

Perpetuating illness mechanisms are often conceptualized as ‘vicious cycles’, which highlights the non-linear patterns of causality characteristic of these disorders. Two simplified examples of chronic ‘rest’ illness behaviours are shown in figure 1. (adapted from (Brazier D.K. & Venning H.E., 1997) . Other people adopt a pattern of trying to achieve a lot on ‘good days’ which results in exhaustion for days following and a flare up of symptoms, (sometimes called ‘Boom-Bust’).

Depression, PTSD, Sleep Disorders, and Anxiety Disorders can also perpetuate functional disorders and should be identified and treated where they are present. Side effects or withdrawal effects of medication often need to be considered. Iatrogenic factors such as lack of a clear diagnosis, not feeling believed or not taken seriously by a healthcare professional, multiple (invasive) diagnostic procedures, ineffective treatments and not getting an explanation for symptoms can increase worry and unhelpful illness behaviours. Unnecessary medical interventions (tests, surgeries or drugs) can also cause harm and worsen symptoms.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of the functional disorder(s) is usually made in the healthcare setting most often by a doctor - this could be a primary care physician or family doctor, hospital physician or specialist in the area of psychosomatic medicine or a consultant-liaison psychiatrist. The primary care physician or family doctor will generally play an important role in coordinating treatment with a secondary care clinician if necessary.

The diagnosis is essentially clinical, whereby the clinician undertakes a thorough medical and mental health history and physical examination. Diagnosis should be based on the nature of the presenting symptoms, and is a “rule in” as opposed to “rule out” diagnosis - this means it is based on the presence of positive symptoms and signs that follow a characteristic pattern. There is usually a process of clinical reasoning to reach this point and assessment might require several visits, ideally with the same doctor.

In the clinical setting, there are no laboratory or imaging tests that can consistently be used to diagnose the condition(s); however, as is the case with all diagnoses, often additional diagnostic tests (such as blood tests, or diagnostic imaging) will be undertaken to consider the presence of underlying disease. There are however diagnostic criteria that can be used to help a doctor assess whether an individual is likely to suffer from a particular functional syndrome. These are usually based on the presence or absence of characteristic clinical signs and symptoms. Self-report questionnaires may also be used/helpful.

It is not unusual for a functional disorder to coexist with another diagnosis (for example functional seizures can coexist with Epilepsy (Reuber et al 2003), or Irritable Bowel Syndrome with Inflammatory Bowel Disease (Fairbrass 2020).This is important to recognise as additional treatment approaches might be indicated in order that the patient achieves adequate relief from their symptoms.

The diagnostic process is considered an important step in order for treatment to move forward successfully. When healthcare professionals are giving a diagnosis and carrying out treatment, it is important to communicate openly and honestly and not to fall into the trap of dualistic concepts – that is “either mental or physical” thinking; or attempt to “reattribute” symptoms to a predominantly psychosocial cause (Gask et al., 2011) . It often important to recognise the need to cease unnecessary additional diagnostic testing if a clear diagnosis has been established (Brown, 2013).

Treatment

Functional disorders can be treated successfully and are considered reversible conditions. Treatment strategies should integrate biological, psychological and social perspectives. Most affected people benefit from support and encouragement in this process, ideally through a multi-disciplinary team with expertise in treating functional disorders. Family members or friends may also be helpful in supporting recovery.

With regard to self-management, there are many basic things that can be done to optimise recovery. Learning about and understanding the condition is helpful in itself (van Gils et.al. 2016). Many people are able to use bodily complaints as a signal to slow down and reassess their balance between exertion and recovery. Bodily complaints can be used as a signal to begin incorporating stress reduction and balanced lifestyle measures (routine, regular activity and relaxation, diet, social engagement) that can help reduce symptoms and are central to improving quality of life. Mindfulness practice can be helpful for some people (Lakhan and Schofield, 2013). The aim of treatment overall is to first create the conditions necessary for recovery, and then plan a programme of rehabilitation to re-train mind-body connections making use of the body’s ability to change. Particular strategies can be taught to manage bowel symptoms, pain or seizures (Henningsen, Zipfel and Herzog, 2007). Though there is generally little focus on the role of medication in treatment, medication to reduce symptoms might be indicated in some instances, for example where mood or pain is a significant issue, preventing adequate engagement in rehabilitation. It is important to address accompanying factors such as sleep disorders, pain, depression and anxiety, and concentration difficulties.

Physiotherapy may be relevant for exercise and activation programs, or when weakness or pain is a problem. Psychotherapy might be helpful to explore a pattern of thoughts, actions and behaviours that could be driving a negative cycle – for example tackling illness expectations or preoccupations about symptoms (Hennemann et al 2022). Family members or friends can also be helpful in supporting recovery. The body of research around evidence-based treatment in functional disorders is growing (Henningson et al 2018). Some existing evidence-based treatments include; physiotherapy and Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) for Functional Neurological Disorder (Goldstein et al 2022; Nielsen et al 2014); and dietary modification or gut targeting agents for Irritable Bowel Syndrome (Fukudo 2021).

For some patients, especially those who have lived with a functional disorder for many years, realistic treatment includes a focus on management of symptoms and improvements in quality of life. Acceptance of symptoms and the limitations they cause can be important in these situations, and most people are able to see some improvement in their condition. Supportive relationships with the healthcare team are key to this.

Controversies/stigma

Despite some progress in the last decade, people with functional disorders continue to suffer subtle and overt forms of discrimination by clinicians, researchers and the public. Stigma is a common experience for individuals who present with functional symptoms and is often driven by historical narratives and factual inaccuracies. Given that functional disorders do not usually have specific biomarkers or findings on structural imaging that are typically undertaken in routine clinical practice, this leads to potential for symptoms to be misunderstood, invalidated, or dismissed, leading to adverse experiences when individuals are seeking help (Looper and Kirmayer 2004).

People with functional disorders frequently describe experiences of doubt, blame, and of being seen as less ‘genuine’ than those with other disorders. Some clinicians perceive those individuals with functional disorders are imagining their symptoms, are malingering, or doubt the level of voluntary control they have over their symptoms. As a result, individuals with these disorders often wait long periods of time to be seen by specialists and receive appropriate treatment (Herzog et al 2018). This is changing, and patient membership organisations/advocate groups have been instrumental in gaining recognition for individuals with these disorders (fndhope.org; www.theibsnetwork.org).

Part of this stigma is also driven by theories around “mind body dualism”, which frequently surfaces as an area of importance for patients, researchers and clinicians in the realm of functional disorders. Artificial separation of the mind/brain/body (for example the use of phrases such as; “physical versus psychological” or “organic versus non-organic”) furthers misunderstanding and misconceptions around these disorders, and only serves to hinder progress in scientific domain and for patients seeking treatment. Current research is moving away from dualistic theories, and recognising the importance of the whole person, both mind and body, in diagnosis and treatment of these conditions.

Further research (future directions)

Directions for research involve understanding more about the processes underlying functional disorders, identifying what leads to symptom persistence and improving integrated care/treatment pathways for patients.

Research into the biological mechanisms which underpin functional disorders is ongoing. Understanding how stress effects the body over a lifetime, for example via the immune, endocrine and autonomic nervous systems, is important (Dantzer et.al. 2014, Boeckxstaens et al 2017, Ying-Chih et.al 2020, Tak et. al. 2011, Nater et al. 2011). Subtle dysfunctions of these systems, for example through low grade chronic inflammation, or dysfunctional breathing patterns, are increasingly thought to underlie functional disorders and their treatment (Irwin et al. 2011, Strawbridge et al. 2019, Gold, 2011). However, more research is needed before these theoretical mechanisms can be used clinically to guide treatment for an individual patient.

To address these gaps, there are several networks of researchers who work in the area of Functional Disorders (https://www.euronet-soma.eu/; https://etude-itn.eu/; Löwe et al., 2022). It is hoped that such networks will integrate cross-disciplinary knowledge and research, translating this into better services and supports for functional disorders, and ultimately improve care for patients.

References

APA., 2022. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Washington: American Psychiatric Publications Inc.

Ballering, A., Muijres, D., Uijen, A., Rosmalen, J., & olde Hartman, T. (2021). Sex differences in the trajectories to diagnosis of patients presenting with common somatic symptoms in primary care: an observational cohort study. Journal Of Psychosomatic Research, 149, 110589. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2021.110589

Barsky, A. J., Goodson, J. D., Lane, R. S., & Cleary, P. D. (1988). The amplification of somatic symptoms. Psychosomatic medicine, 50(5), 510-519.

Barron, E. and Rotge, J., 2019. Talking about “psychogenic nonepileptic seizure” is wrong and stigmatizing. Seizure, 71, pp.6-7.

Boeckxstaens, G. E., & Wouters, M. M. (2017). Neuroimmune factors in functional gastrointestinal disorders: A focus on irritable bowel syndrome. Neurogastroenterology & Motility, 29(6), e13007.

Bourke, J. H., Langford, R. M., & White, P. D. (2015). The common link between functional somatic syndromes may be central sensitisation. Journal of psychosomatic research, 78(3), 228-236.

Bradford, K., Shih, W., Videlock, E., Presson, A., Naliboff, B., Mayer, E., & Chang, L. (2012). Association Between Early Adverse Life Events and Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Clinical Gastroenterology And Hepatology, 10(4), 385-390.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2011.12.018

Brazier, D. K., & Venning, H. E. (1997). Conversion disorders in adolescents: a practical approach to rehabilitation. British journal of rheumatology, 36(5), 594-598.

Brown, R. J. (2013). Explaining the unexplained. The Psychologist.

Canavan, C., West, J. and Card, T., 2014. The epidemiology of irritable bowel syndrome. Clinical Epidemiology, p.71.

Chambers, D., Bagnall, A., Hempel, S. and Forbes, C., 2006. Interventions for the Treatment, Management and Rehabilitation of Patients with Chronic Fatigue Syndrome/ Myalgic Encephalomyelitis: An Updated Systematic Review. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 99(10), pp.506-520.

Claréus, Benjamin, and Renström, Emma A. "Physicians’ gender bias in the diagnostic assessment of medically unexplained symptoms and its effect on patient–physician relations." Scandinavian journal of psychology 60.4 (2019): 338-347.

Cohen, H., Neumann, L., Haiman, Y., Matar, M., Press, J., & Buskila, D. (2002). Prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder in fibromyalgia patients: Overlapping syndromes or post-traumatic fibromyalgia syndrome?. Seminars In Arthritis And Rheumatism, 32(1), 38-50. doi: 10.1053/sarh.2002.33719

Dantzer, R., Heijnen, C. J., Kavelaars, A., Laye, S., & Capuron, L. (2014). The neuroimmune basis of fatigue. Trends in neurosciences, 37(1), 39-46.

Euronet-Soma. 2022. EURONET-SOMA. [online] Available at: <https://www.euronet-soma.eu/> [Accessed 29 May 2022].

Fairbrass, K., Costantino, S., Gracie, D., & Ford, A. (2020). Prevalence of irritable bowel syndrome-type symptoms in patients with inflammatory bowel disease in remission: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Gastroenterology &Amp; Hepatology, 5(12), 1053-1062. doi: 10.1016/s2468-1253(20)30300-9

Fischer, S., Skoluda, N., Ali, N., Nater, U. M., & Mewes, R. (2022). Hair cortisol levels in women with medically unexplained symptoms. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 146, 77-82.

FND Hope International. 2022. HOME FND Hope - FND Hope International. [online] Available at: <https://fndhope.org/> [Accessed 29 May 2022].

Fukudo, S., Okumura, T., Inamori, M., Okuyama, Y., Kanazawa, M., Kamiya, T., Sato, K., Shiotani, A., Naito, Y., Fujikawa, Y., Hokari, R., Masaoka, T., Fujimoto, K., Kaneko, H., Torii, A., Matsueda, K., Miwa, H., Enomoto, N., Shimosegawa, T. and Koike, K., 2021. Evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for irritable bowel syndrome 2020. Journal of Gastroenterology, 56(3), pp.193-217.

Garakani, A., Win, T., Virk, S., Gupta, S., Kaplan, D., & Masand, P. (2003). Comorbidity of Irritable Bowel Syndrome in Psychiatric Patients: A Review. American Journal Of Therapeutics, 10(1), 61-67. doi: 10.1097/00045391-200301000-00014

Gask, L., Dowrick, C., Salmon, P., Peters, S., & Morriss, R. (2011). Reattribution reconsidered: narrative review and reflections on an educational intervention for medically unexplained symptoms in primary care settings. Journal of psychosomatic research, 71(5), 325-334.

Herzog A, Shedden-Mora MC, Jordan P, Löwe B. Duration of untreated illness in patients with somatoform disorders. J Psychosom Res. 2018 Apr;107:1-6. doi:

van Gils, A., Schoevers, R. A., Bonvanie, I. J., Gelauff, J. M., Roest, A. M., & Rosmalen, J. G. (2016). Self-help for medically unexplained symptoms: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychosomatic medicine, 78(6), 728-739.

Gold, A. R. (2011). Functional somatic syndromes, anxiety disorders and the upper airway: a matter of paradigms. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 15(6), 389-401.

Goldstein, L., Robinson, E., Chalder, T., Reuber, M., Medford, N., Stone, J., Carson, A., Moore, M. and Landau, S., 2022. Six-month outcomes of the CODES randomised controlled trial of cognitive behavioural therapy for dissociative seizures: A secondary analysis. Seizure, 96, pp.128-136.

Haller, H., Cramer, H., Lauche, R. and Dobos, G., 2015. Somatoform Disorders and Medically Unexplained Symptoms in Primary Care. Deutsches Ärzteblatt international,.

Hennemann, S., Böhme, K., Kleinstäuber, M., Baumeister, H., Küchler, A., Ebert, D. and Witthöft, M., 2022. Internet-based CBT for somatic symptom distress (iSOMA) in emerging adults: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 90(4), pp.353-365.

Henningsen, P., Zipfel, S. and Herzog, W., 2007. Management of functional somatic syndromes. The Lancet, 369(9565), pp.946-955.

Henningsen, P., Zipfel, S., Sattel, H. and Creed, F., 2018. Management of Functional Somatic Syndromes and Bodily Distress. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 87(1), pp.12-31.

Henningsen, P., Gündel, H., Kop, W. J., Löwe, B., Martin, A., Rief, W., ... & Van den Bergh, O. (2018). Persistent physical symptoms as perceptual dysregulation: a neuropsychobehavioral model and its clinical implications. Psychosomatic medicine, 80(5), 422-431.

Herzog, A., Shedden-Mora, M. C., Jordan, P., & Löwe, B. (2018). Duration of untreated illness in patients with somatoform disorders. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 107, 1-6.

https://etude-itn.eu/. 2022. https://etude-itn.eu/. [online] Available at: <https://etude-itn.eu/> [Accessed 29 May 2022].

https://www.theibsnetwork.org/. 2022. https://www.theibsnetwork.org/support-groups/. [online] Available at: <https://www.theibsnetwork.org/> [Accessed 29 May 2022].

Isaac, M., Janca, A., Burke, K. C., e Silva, J. A. C., Acuda, S. W., Altamura, C., ... & Tacchin, G. (1995). Medically unexplained somatic symptoms in different cultures. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 64(2), 88-93.

Irwin, M. R. (2011). Inflammation at the intersection of behavior and somatic symptoms. Psychiatric Clinics, 34(3), 605-620.

Kato, K., Sullivan, P. F., Evengård, B., & Pedersen, N. L. (2006). Premorbid predictors of chronic fatigue. Archives of general psychiatry, 63(11), 1267-1272.

Kingma EM, de Jonge P, Ormel J, Rosmalen JG. Predictors of a functional somatic syndrome diagnosis in patients with persistent functional somatic symptoms. Int J Behav Med. 2013 Jun;20(2):206-12. doi: 10.1007/s12529-012-9251-4. PMID: 22836483.

Konnopka, A., Schaefert, R., Heinrich, S., Kaufmann, C., Luppa, M., Herzog, W., & König, H.-H. (2012). Economics of medically unexplained symptoms: A systematic review of the literature. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 81(5), 265–275. https://doi.org/10.1159/000337349

Kozlowska, K. (2013). Functional somatic symptoms in childhood and adolescence. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 26(5), 485-492.

Lacourt, T. E., Vichaya, E. G., Chiu, G. S., Dantzer, R., & Heijnen, C. J. (2018). The high costs of low-grade inflammation: persistent fatigue as a consequence of reduced cellular-energy availability and non-adaptive energy expenditure. Frontiers in behavioral neuroscience, 78.

Lakhan, S. and Schofield, K., 2013. Mindfulness-Based Therapies in the Treatment of Somatization Disorders: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS ONE, 8(8), p.e71834.

Looper, Karl J., and Laurence J. Kirmayer. "Perceived stigma in functional somatic syndromes and comparable medical conditions." Journal of psychosomatic research 57.4 (2004): 373-378.

Löwe, B., Andresen, V., Van den Bergh, O., Huber, T., von dem Knesebeck, O., Lohse, A., Nestoriuc, Y., Schneider, G., Schneider, S., Schramm, C., Ständer, S., Vettorazzi, E., Zapf, A., Shedden-Mora, M. and Toussaint, A., 2022. Persistent SOMAtic symptoms ACROSS diseases — from risk factors to modification: scientific framework and overarching protocol of the interdisciplinary SOMACROSS research unit (RU 5211). BMJ Open, 12(1), p.e057596.

Löwe, B., Levenson, J., Depping, M.et al., (2022). Somatic symptom disorder: A scoping review on the empirical evidence of a new diagnosis. Psychological Medicine 52:632-48

Ludwig, L., Pasman, J., Nicholson, T., Aybek, S., David, A., & Tuck, S. et al. (2018). Stressful life events and maltreatment in conversion (functional neurological) disorder: systematic review and meta-analysis of case-control studies. The Lancet Psychiatry, 5(4), 307-320. doi: 10.1016/s2215-0366(18)30051-8

Macina, C., Bendel, R., Walter, M., & Wrege, J. S. (2021). Somatization and Somatic Symptom Disorder and its overlap with dimensionally measured personality pathology: A systematic review. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 151, 110646.

Marques, A., Santo, A., Berssaneti, A., Matsutani, L. and Yuan, S., 2017. Prevalence of fibromyalgia: literature review update. Revista Brasileira de Reumatologia (English Edition), 57(4), pp.356-363.

McBeth, J., Tomenson, B., Chew-Graham, C., Macfarlane, G., Jackson, J., Littlewood, A. and Creed, F., 2015. Common and unique associated factors for medically unexplained chronic widespread pain and chronic fatigue. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 79(6), pp.484-491.

McKenzie YA, Bowyer RK, Leach H, Gulia P, Horobin J, O'Sullivan NA, Pettitt C, Reeves LB, Seamark L, Williams M, Thompson J, Lomer MC; (IBS Dietetic Guideline Review Group on behalf of Gastroenterology Specialist Group of the British Dietetic Association). British Dietetic Association systematic review and evidence-based practice guidelines for the dietary management of irritable bowel syndrome in adults (2016 update). J Hum Nutr Diet. 2016 Oct;29(5):549-75. doi: 10.1111/jhn.12385. Epub 2016 Jun 8. PMID: 27272325.

M Nater, U., Fischer, S., & Ehlert, U. (2011). Stress as a pathophysiological factor in functional somatic syndromes. Current Psychiatry Reviews, 7(2), 152-169.

Nielsen, G., Stone, J., Matthews, A., Brown, M., Sparkes, C., Farmer, R., Masterton, L., Duncan, L., Winters, A., Daniell, L., Lumsden, C., Carson, A., David, A. and Edwards, M., 2014. Physiotherapy for functional motor disorders: a consensus recommendation. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry, 86(10), pp.1113-1119.

Nijs, J., Van Wilgen, C. P., Van Oosterwijck, J., van Ittersum, M., & Meeus, M. (2011). How to explain central sensitization to patients with ‘unexplained’chronic musculoskeletal pain: practice guidelines. Manual therapy, 16(5), 413-418.

Nimnuan, C., Hotopf, S. and Wessely, s., 2001. Medically unexplained symptoms: an epidemiological study in seven specialities. Journal of psychosomatic research, Jul;51(1):361-7.

Petersen, M., Schröder, A., Jørgensen, T., Ørnbøl, E., Dantoft, T., Eliasen, M., Carstensen, T., Falgaard Eplov, L. and Fink, P., 2019. Prevalence of functional somatic syndromes and bodily distress syndrome in the Danish population: the DanFunD study. Scandinavian Journal of Public

Porcelli, P., Michael Bagby, R., Taylor, G., De Carne, M., Leandro, G., & Todarello, O. (2003). Alexithymia as Predictor of Treatment Outcome in Patients with Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders. Psychosomatic Medicine, 65(5), 911-918. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000089064.13681.3bHealth, 48(5), pp.567-576.

Reuber, M., Qurishi, A., BAUER, J., Helmstaedter, C., Fernandez, G., Widman, G., & Elger, C. E. (2003). Are there physical risk factors for psychogenic non-epileptic seizures in patients with epilepsy?. Seizure, 12(8), 561-567.

Sperber AD, Bangdiwala SI, Drossman DA, et al (2011). Worldwide Prevalence and Burden of Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders, Results of Rome Foundation Global Study. Gastroenterology;160:99-114 e3.

Stone, J., Carson, A., Duncan, R., Roberts, R., Coleman, R., & Warlow, C. et al. (2011). Which neurological diseases are most likely to be associated with “symptoms unexplained by organic disease”. Journal Of Neurology, 259(1), 33-38. doi: 10.1007/s00415-011-6111-0

Strawbridge, R., Sartor, M. L., Scott, F., & Cleare, A. J. (2019). Inflammatory proteins are altered in chronic fatigue syndrome—a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 107, 69-83.

Tak, L. M., Cleare, A. J., Ormel, J., Manoharan, A., Kok, I. C., Wessely, S., & Rosmalen, J. G. (2011). Meta-analysis and meta-regression of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis activity in functional somatic disorders. Biological psychology, 87(2), 183-194.

Thomas, N., Gurvich, C., Huang, K., Gooley, P. R., & Armstrong, C. W. (2022). The underlying sex differences in neuroendocrine adaptations relevant to Myalgic Encephalomyelitis Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology, 66, 100995.

Wessely, S., Nimnuan, C., & Sharpe, M. (1999). Functional somatic syndromes: one or many?. The Lancet, 354(9182), 936-939. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(98)08320-2

WHO 2022 Icd.who.int. ICD-11. [online] Available at: <https://icd.who.int/en> [Accessed 29 May 2022].

Ying-Chih, C., Yu-Chen, H., & Wei-Lieh, H. (2020). Heart rate variability in patients with somatic symptom disorders and functional somatic syndromes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 112, 336-

___________________________________________________________________________________

Acknowledgement: This text has been developed within the ETUDE innovation training network and will be used for publication on international Wikipedia pages.